The World of "Mountain Sports": A Visual Thesaurus

As you dive into any hobby, occupation, or interest, there becomes a stronger and stronger need to get specific when talking to others in the same space. Once a topic you thought was quite simple opens up into a rabbit hole of niches and varietals, requiring ever more specific terminology, acronyms, and jargon.

It serves a great utility for the "in-crowd", allowing them to understand one another with clarity and speed, and hide lengthy explanations or nuances behind simple phrases and words. Yet, it immediately puts up a wall between them and those outside of their space.

As I have written more, and had more eyes on the words I have chosen to use in these trip reports and stories, I have gotten many similar questions repeated from lots of different readers. The large majority of these questions stemmed from a misunderstanding of a word used in an unfamiliar way or one that was not a part of their vocabulary at all! This piece aims to begin to peel back some of the onion layers that make up "mountain sports" by first unfurling a map of what that phrase even includes.

For the purposes of brevity, for now, I will be leaving out any sports that don't primarily take place with the use of your foot to the ground. Sorry, mountain-biking, base jumping, and skiing... but there are too many nested rabbit holes for a single piece.

"Mountain sports" simply means any sport that takes place in the mountains. To quote Wikipedia: "[Mountain sport] is one of several types of sport that take place in hilly or mountainous terrain."

A decent take at a generalized term for those of us who choose to recreate where the ground gets a bit steeper. However, mountains are big, they go through significant weather changes during the course of the year, and exist in countless biomes and variations. To make it even more complicated, most "mountain athletes" participate in a wide variety of these sports to cover for those yearly weather changes and the intensities of each activity. So when talking about these activities it does one no good to simply say "Hey, want to go mountain sport with me this weekend?" you must get more specific! How about... "Hey, want to go climb in the mountains with me this weekend?" we're getting somewhere, but even with knowledge of the specific destination, multiple routes might exist, taking vastly different paths and skills to succeed! Would this trip require special gear? Would it require camping? A whole can of worms is opened!

Something you might be more likely to hear is:

"Hey, I've been looking at peak X, the west face is a 5.9 climb, but east ridge looks like a pretty chill scramble. It's a big approach, 30 miles round trip, but if we do the scramble I think we could fast-pack it.

There's a ton of information baked into a question like this that, to an "expert", would be extremely helpful in making a decision, but for an outsider, it might need some follow-up. So, in the interest of pulling back the veil a bit, let's start with the most high-level topic: What "sports" make up the plural in "mountain sports"?

What are "mountain sports"?

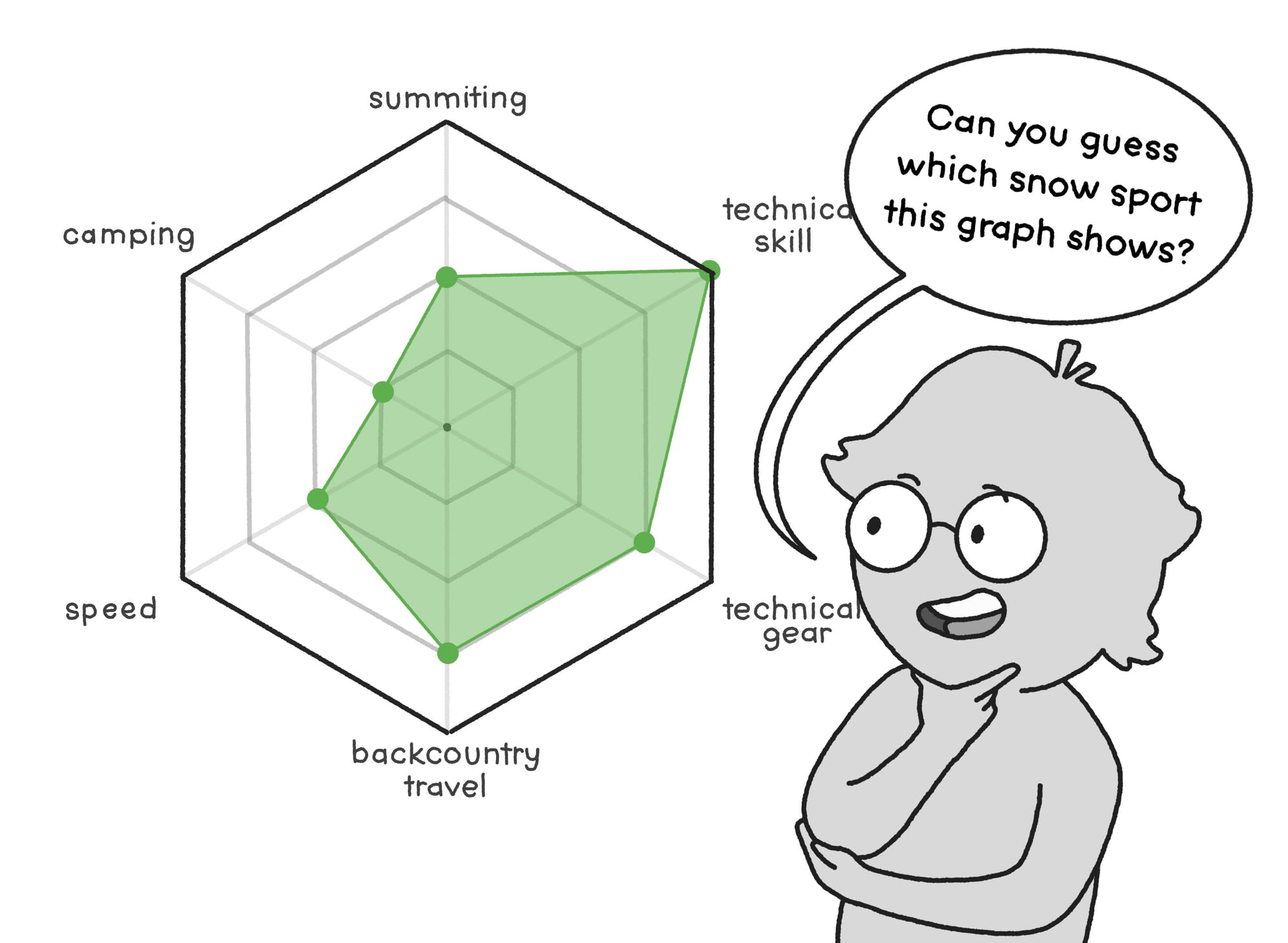

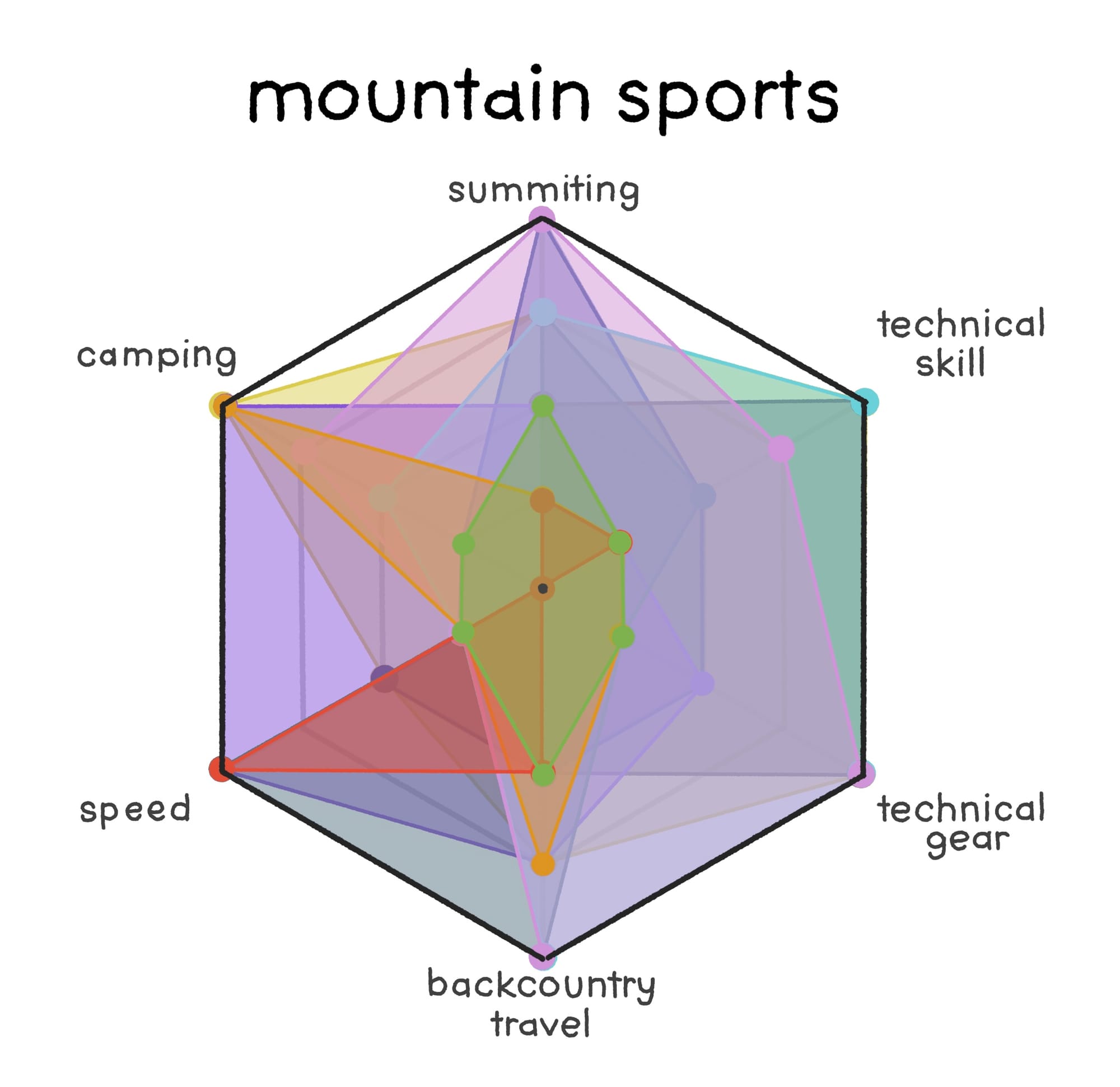

In the continued interest in brevity, I have compiled a dozen different variations of mountain sports and plotted them all on a six-dimensional graph to help you understand what people mean when they use those terms (and more specifically what I mean when I write them). These are not meant to be deep-dives or comprehensive representations of those sports (which each have their own niches to dive deeper into), but to give a thesaurus to curious outsiders and a fun thing to argue about for pedantic online commenters!

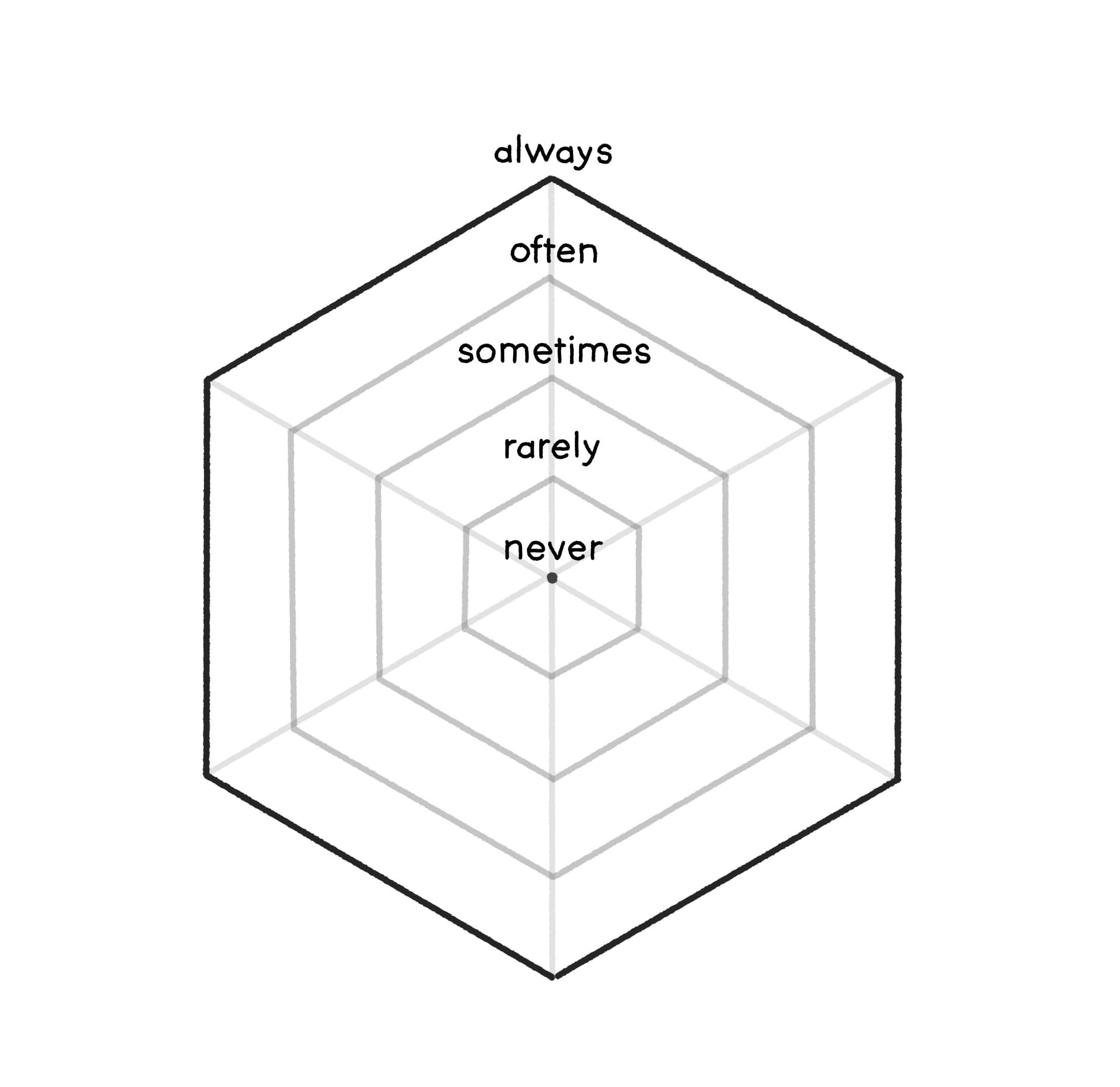

First, lets go over this graph. To try and pry apart the differences between these sports I came up with six different "focuses" we can plot for these activities.

- Summiting

- A focus on achieving the summit or peak of a mountain during the activity

- Technical Skill

- A focus on a technical skill required to perform the activity

- Technical Gear

- A focus on specialization with gear or tools to perform the activity

- Backcountry Travel

- A focus on traveling into the backcountry

- Speed

- A focus on speed as a primary objective during the activity

- Camping

- A focus on multi-day trips that require sleeping during the activity

For each "focus" I will plot a score of 0-4 on the graph as defined below, a 0 meaning "this activity never focuses on this" and a 4 meaning "this activity always focuses on this" with a few steps in between for ambiguity.

Disclaimer! This does not mean these activities are strict concepts, many people will have different opinions or have done something against one of these graphs. That's fine... this is merely a guide to help you understand what many people mean when they use one of these words.

The "core" activities

Many of these activities build on top of one another, and as such, we must start at the "bottom" with the more fundamental pieces to be able to properly understand the more complex and involved ones.

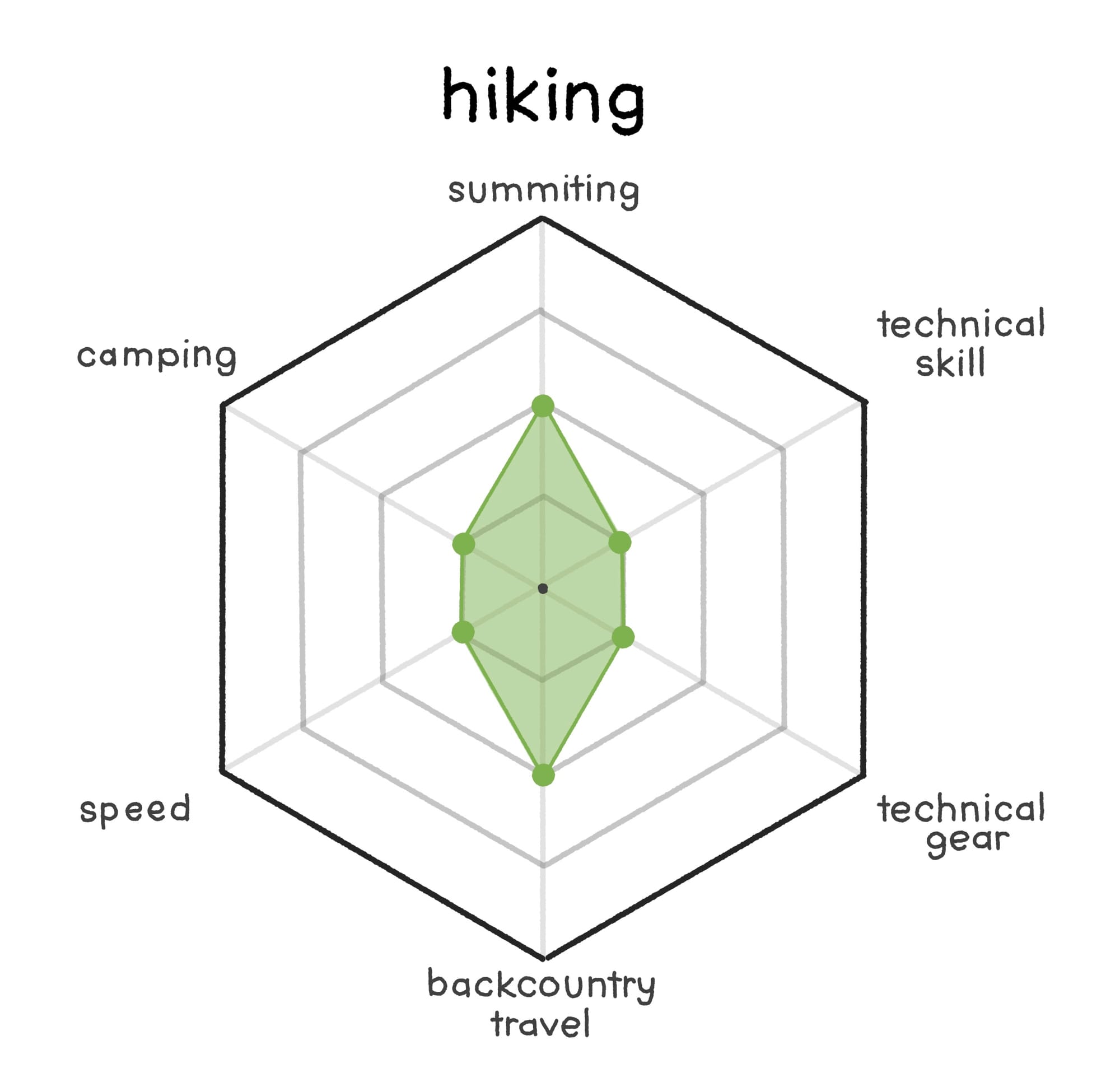

Hiking is perhaps the most fundamental "mountain sport" and definitely the one most people are already acquainted with. (What a good place to start to help us understand the graph). To quote Wikipedia again: "A hike is a long, vigorous walk, usually on trails or footpaths in the countryside."

So, anytime we are walking on a trail outside of human dominated places that counts as a hike!

However, the term is generic enough that often just hearing "I'm going hiking" isn't quite enough to deduce exactly what they will be doing, and the graph reflects that. While someone rarely means that they will be camping, moving very fast, doing something requiring specialized skills or technical gear... we can't count any of them out completely!

Hiking can and does take place on any existing trail. It may be meandering or specifically pointing to a peak. It may be through a well maintained park or through wilderness areas. Hiking is accessible to all no matter the fitness level or intention and, as such, gets a wide usage in the mountain lexicon.

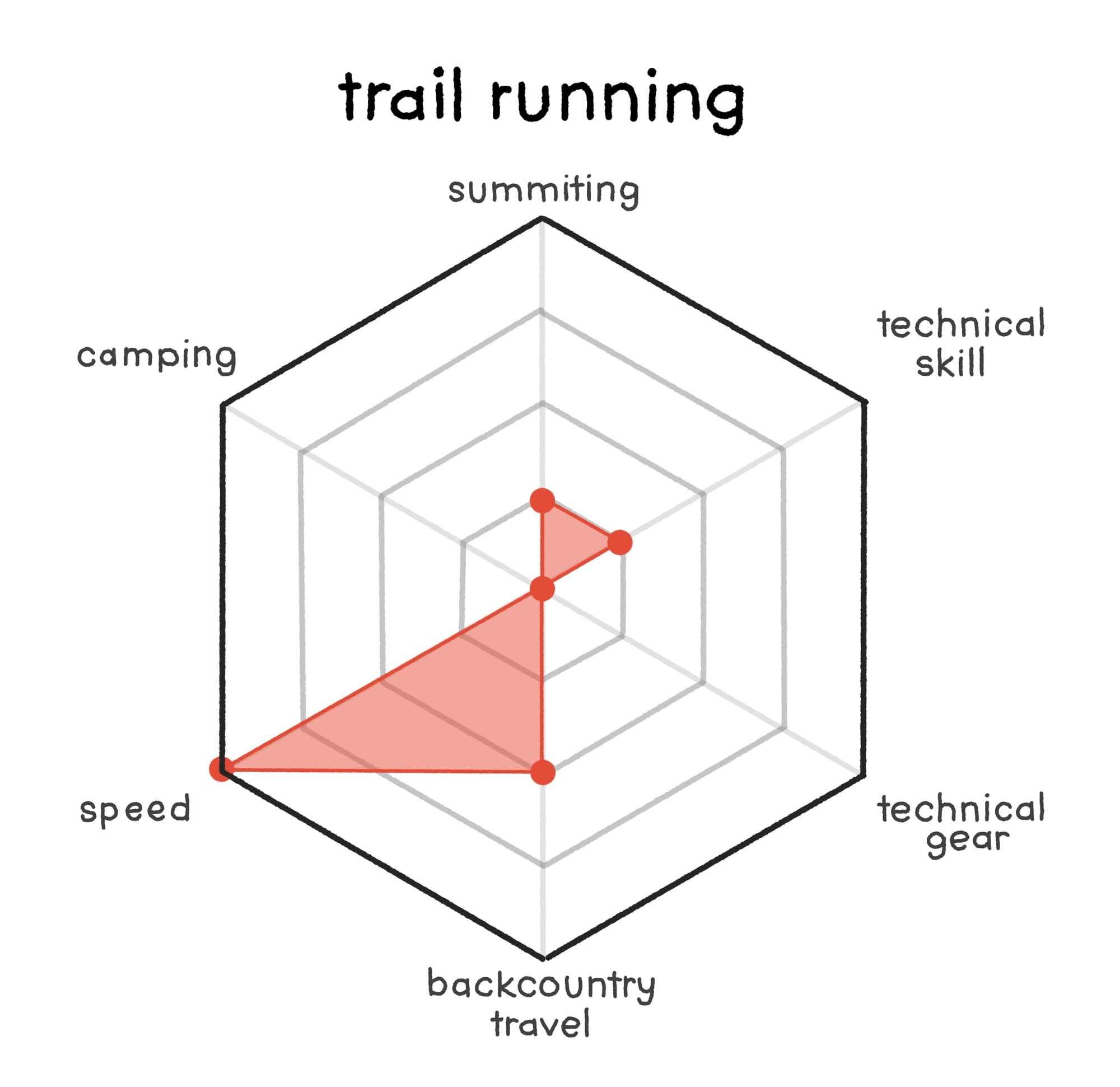

Trail running is a small step away from hiking in many regards – it requires essentially no new skills – just a shift of mindset. To focus on speed over leisure, and a slightly higher bar for required cardiovascular endurance. The graph shows this, taking a few points away here and there and placing all of them into "speed".

Typically, a trail runner doesn't have any intention to camp or carry around gear other than their trail runners (shoes) and a vest, and they tend to prefer rolling trails to rocky ridge lines or steep summit pushes. While the amount of backcountry travel is most of the time quite similar to hiking, the ability to do more miles in the same amount of time often pushes trail runners into this arena more than your average hiker, but only by a bit.

So, when someone talks about trail running you can always tell their goal will be pace, no matter where they are going, they will be thinking about doing it efficiently and quickly.

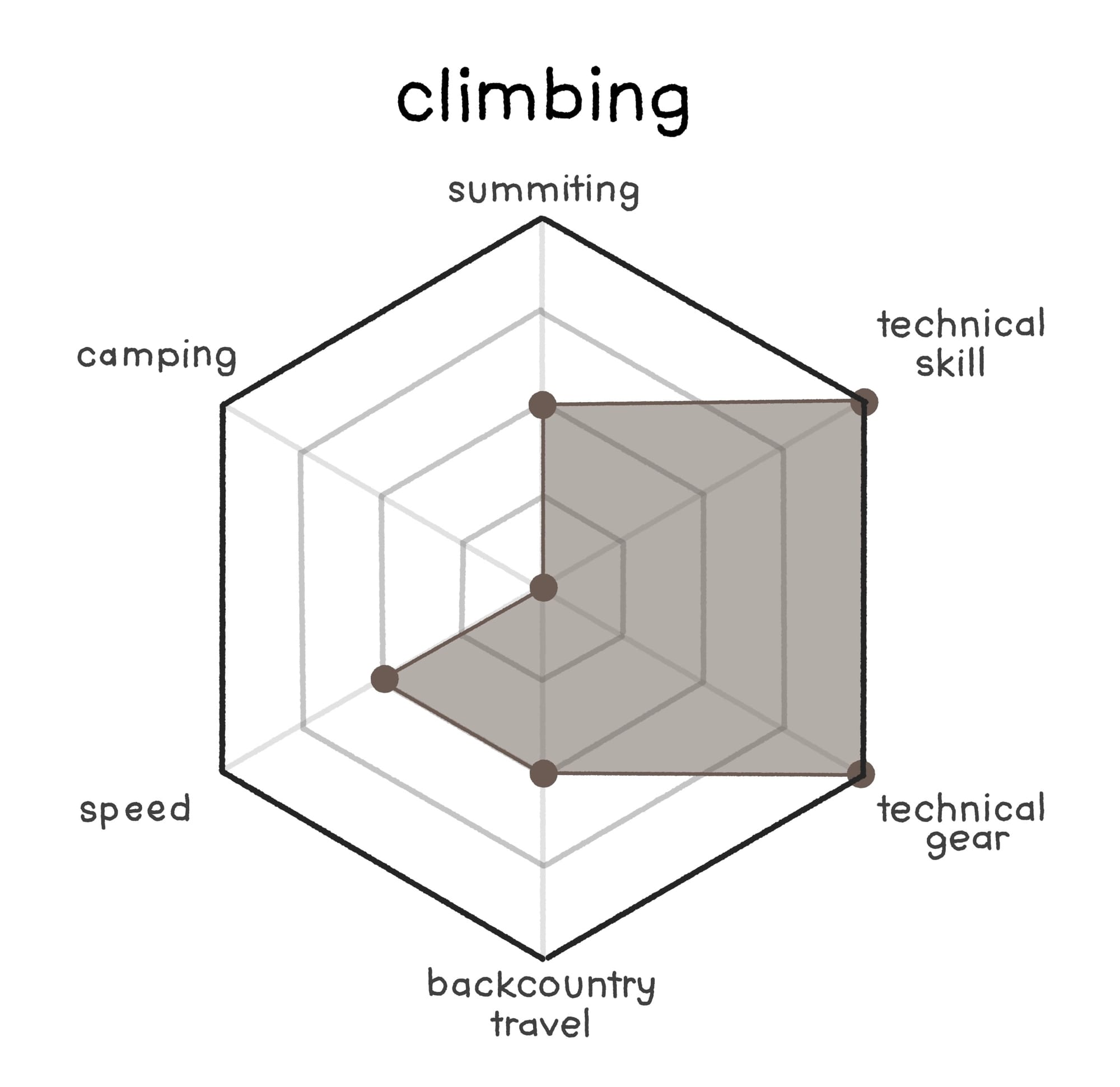

Climbing is the next building block as it is the opposite end of the spectrum from hiking in many regards, but still only consists of fundamental movements. We can use the chart to see at a glance how it differs from hiking. When people talk about "climbing" they are specifically calling out the need for both technical skill and gear in a way that "hiking" does not immediately invoke.

The term climbing is still a very general one though and is probably the most misleading of the bunch. Some people might use the term "climb" to simply mean "ascend", or they might use it in place of one of a deluge of disciplines like rock climbing, ice climbing, mixed climbing (both rock and ice). Even within these disciplines the terms can be fragmented further: Are you climbing a boulder? A single pitch? Many pitches in a row? Are you soloing? No matter the answer to one of these, the term climbing can be used.

A "pitch" is a term used to denote one effort in rope climbing, where the "lead" climber goes ahead before stopping and belaying their follower up. Usually pitches are 20 - 35 meters (about half the length of a normal rope) but can be smaller or longer depending on the wall. A pitch usually ends on a natural feature like a ledge or the top of a wall and has bolts or other natural features to anchor yourself to.

With all of these caveats aside, if you are hearing this term from someone deep in the pits of their own personal mountain sport rabbit hole, they are likely to use it in the way the graph describes. To "climb" a mountain means to tackle it in a way that is not just walking up, but via some more technical route.

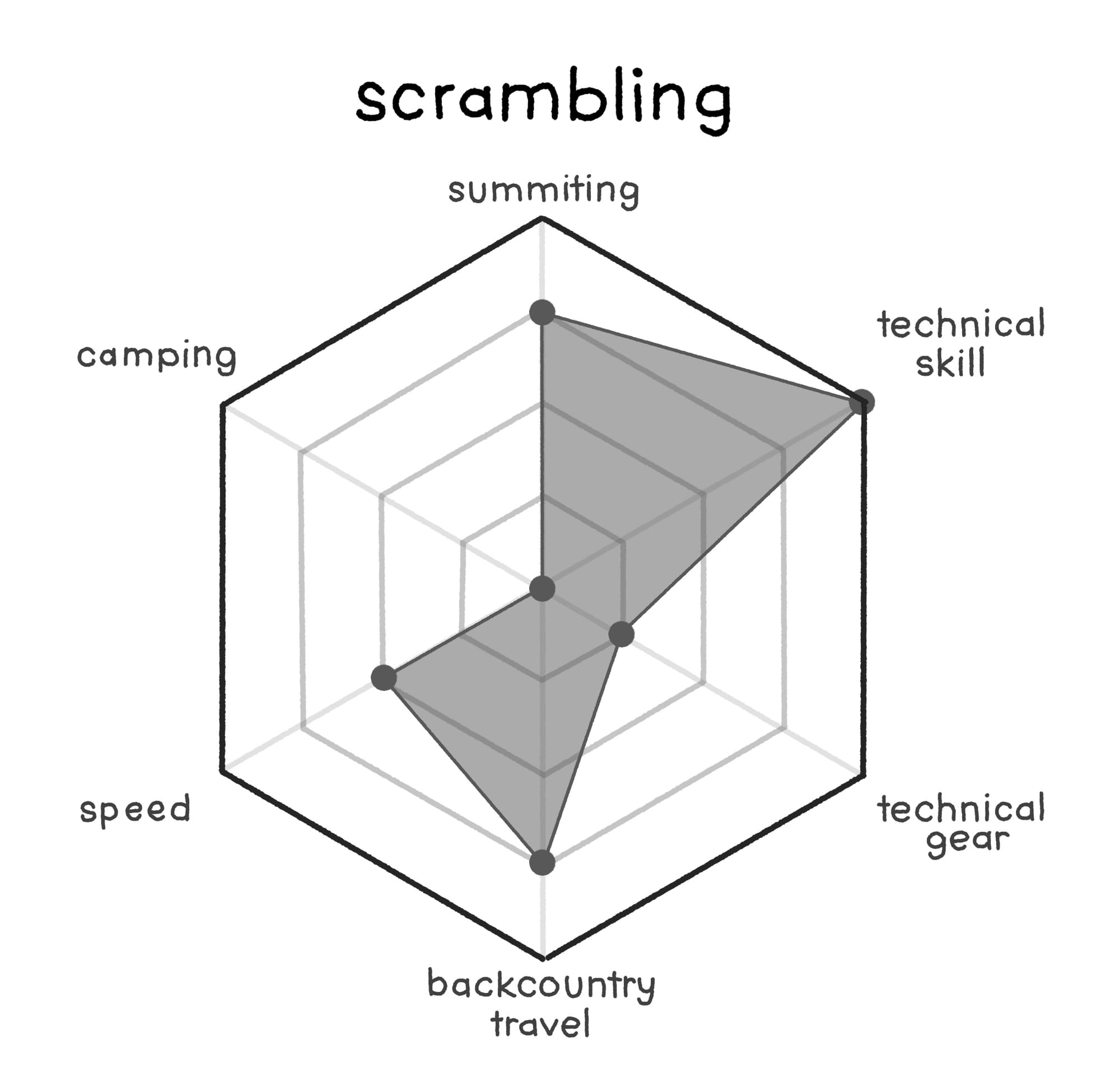

Scrambling is the last core activity and the one that non-mountain people are often the least acquainted with. To a layman it seems the same as climbing, and one might even mistake it with "free soloing".

Scrambling is the practice of "climbing" (why this is so confusing) over easy terrain where you are still more reliant on your feet than your hands, typically only using them to stabilize you or surmount a move or two. It almost never requires technical gear like ropes, bolts, or traditional gear, as the difficultly is considered to be to easy enough not to warrant their weight and slowness.

While the actual technical ability is lower than what most mean when they say climbing the need for technical skill is still always a focus when mentioning scrambling. Most of the time scrambling takes place in the backcountry and off trail, so you must be able to follow a map and the terrain of your own accord. Scrambling is often associated with peaks or ridge lines as that is the primary area where the terrain exists. Many "technical" peaks that do no have a maintained or direct trail to them will require some level of scrambling, which leans this term towards a focus on summiting.

Terrain Difficulty

As a slightly deeper dive into the way us mountain people will distinguish between these core activities, you may hear the terms 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th "class".

These are the loose categorizations that we use to differentiate when something goes from hiking (1st and 2nd class), to scrambling (3rd and 4th class), to climbing (5th class). These buckets are the original designation of the "Yosemite Decimal System" and serve to judge how difficult the terrain will be that you will encounter.

1st class: A maintained hiking trail with no obstacles.

2nd class: A rough hiking trail, often with rocks or large steps that may require the use of your hands for balance in some places.

3rd class: Typically no longer a trail, but instead a loose path of rocks or boulders that can be walked on and will require the use of hands for balance and scrambling. May involve some exposure (steep drops where a fall would be severe).

4th class: Scrambling terrain where hands are used often including some moves that may involve pulling with your upper body. Often with exposure.

5th class: Vertical or near vertical terrain that involves climbing including the prolonged use of your upper body to ascend. Almost always including exposure. Is further broken into a decimal system, 5.0 - 5.15, to denote physical difficulty.

The Next Level In...

These next activities are still fairly common, so you've probably heard of them, but maybe haven't always understood how they differ from the ones already covered. The lines start to get more and more blurry as you get more specific, and overlaps become more apparent. Each of these could probably fit into one of the "core" activities, but categorizing them further helps take some of those open questions away.

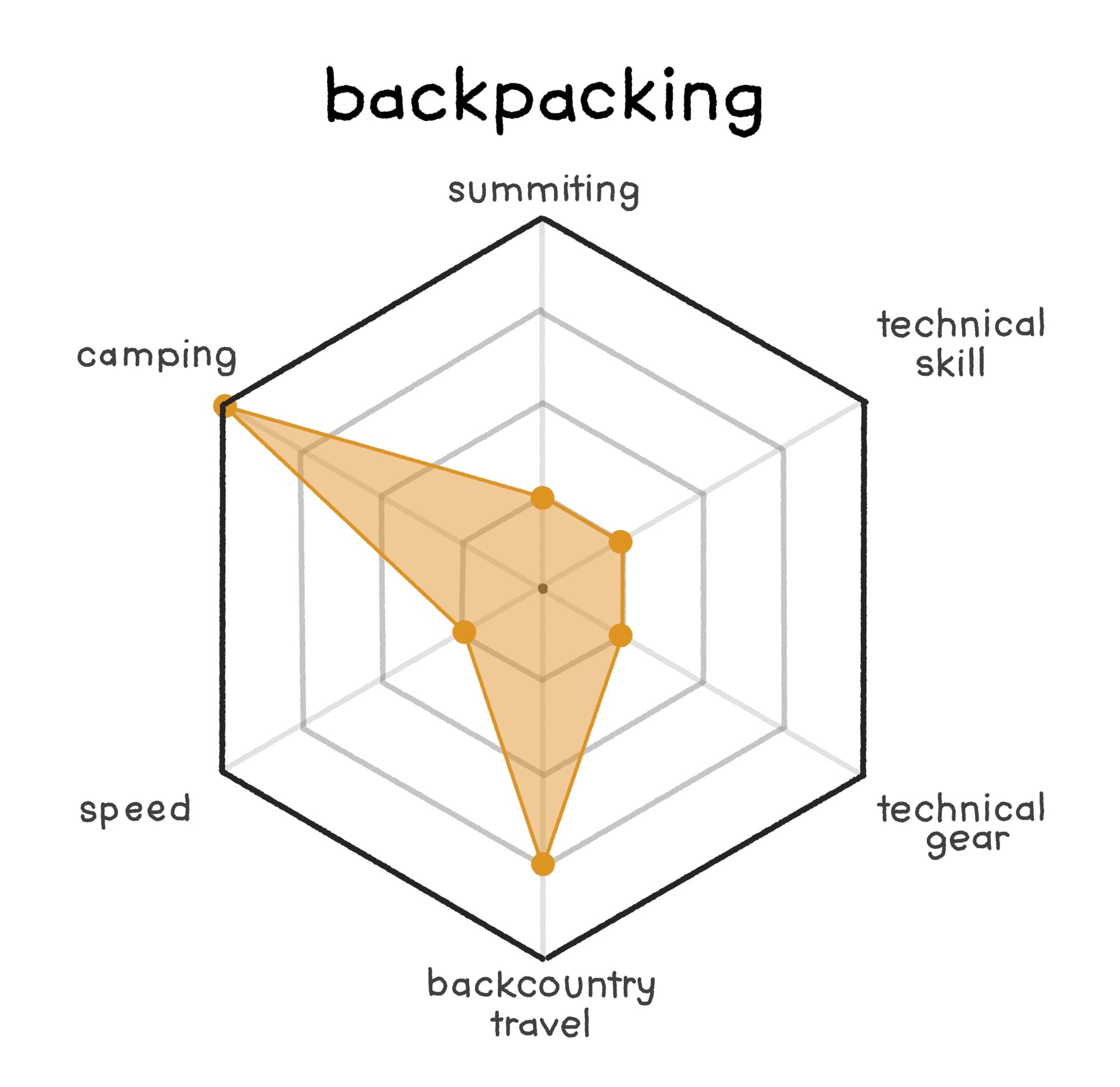

Backpacking is hiking's dirtbag cousin, it shares almost every attribute with a sharp and distinct focus on camping. In fact you can't backpack without camping, usually with a large pack carrying everything you need for a trip. Backpacking has a innate relationship to longer trips, often spanning 2 or more nights, and it's extreme version "through hiking" takes this to the weeks and months range.

For these reasons backpacking often takes place in the backcountry, but with a lower focus on summiting than hiking might have. Instead backpackers tend to spend time on trails that wind between peaks, crossing over mountain passes and valleys to get from point to point. Rarely does a backpacker intend that they are going to do much technical activity, in the cases where you would take backpacking gear to go far into the backcountry to do a technical activity you would use the terms that best describes that instead.

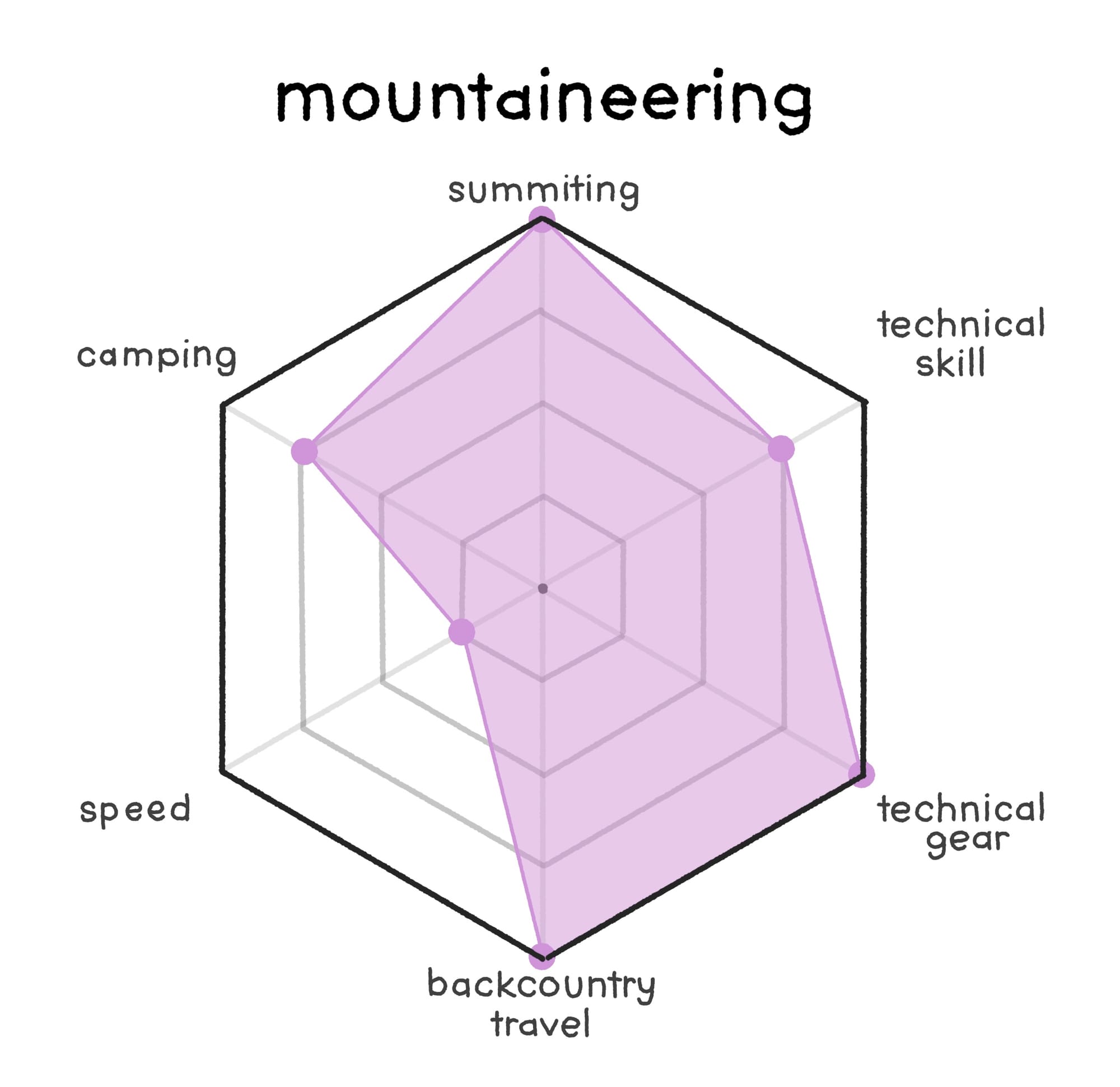

The official definition of "mountaineering" is quite general, to quote our friend Wikipedia one more time: "[Mountaineering] is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains."

By that phrasing it might even be considered the umbrella term for anything that takes you to the peak of a mountain! However when someone is referencing mountaineering they are typically being more specific and targeting the activity of tackling "large" peaks that involve more than just travel on a well defined trail. Often this includes technical skill or gear like glacier crossing, scrambling, steep snow, ice climbing, and more. Not all mountaineering feats are for hardened high-skill athletes, many objectives are just long hikes maybe over snow and maybe ascending above altitudes that start to make travel more strenuous.

High altitude mountaineering is the next step up, but involves all of the same tools, just done in places where the air is very thin, usually at least 5000 meters or more. This is where the Himalayas and tallest peaks in the world are usually introduced and use this term to differentiate themselves.

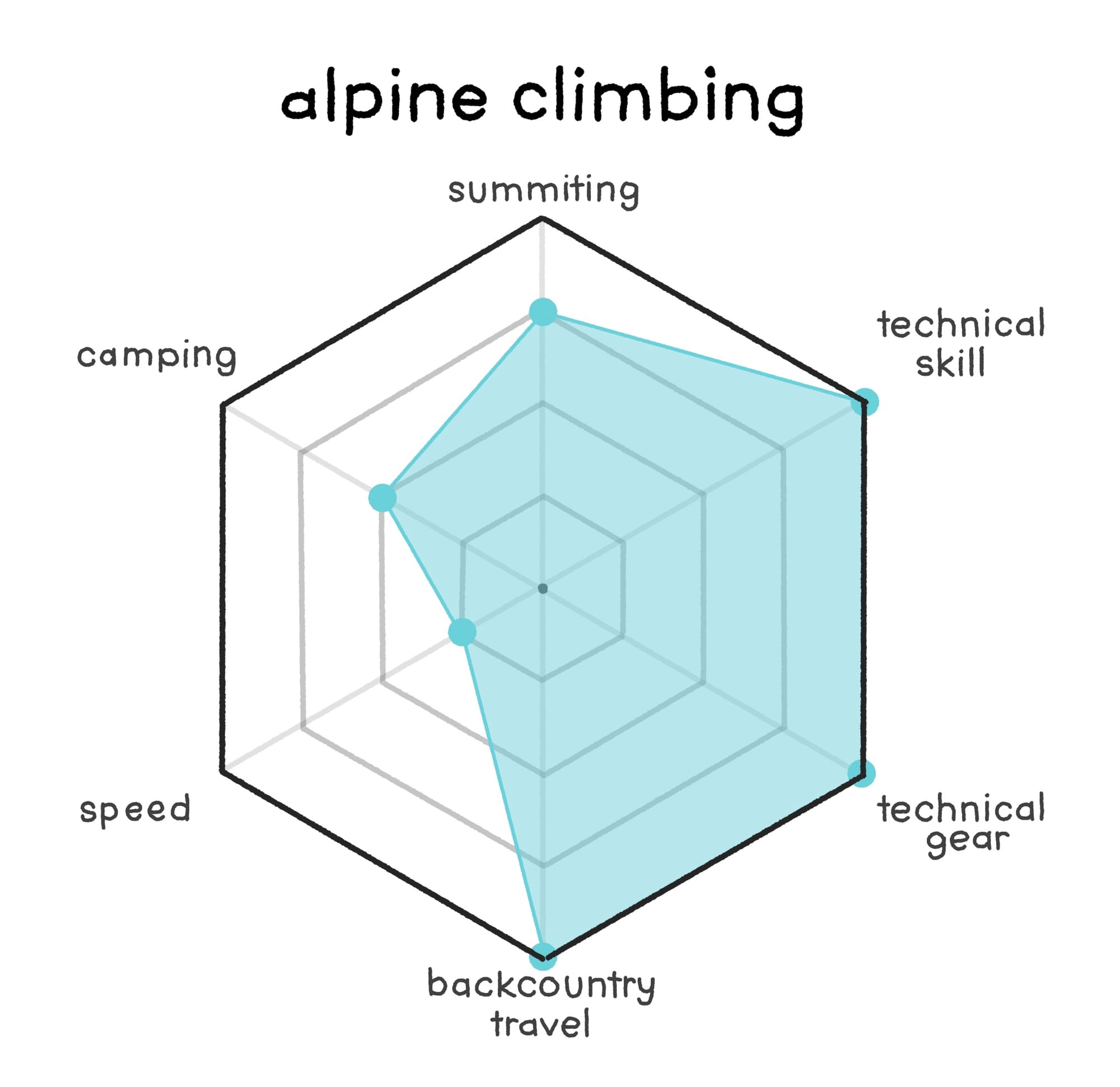

Alpine climbing is plain old climbing's cooler older brother (my bias may be showing). While someone who is "climbing" might mean tackling a roadside boulder or a sport (bolted) crag, alpine climbing always means tackling a larger objective in the backcountry while still focusing on the technical movement of climbing.

For these reasons alpine climbing is more likely to involve camping or multi-day exposure and more often than not is focused on summiting at least one peak. This kind of climbing may involve cross-discipline skill sets including rock climbing, glacier skills, ice climbing, route finding, anything that you might run across while climbing severe terrain well into the backcountry.

The Really Niche Ones

These activities are either newly blossoming or are divisive even within their respective communities. So, when you come across them you might find slightly more complicated definitions or ambiguities, but I'll do my best to introduce you to these interesting and varied sports!

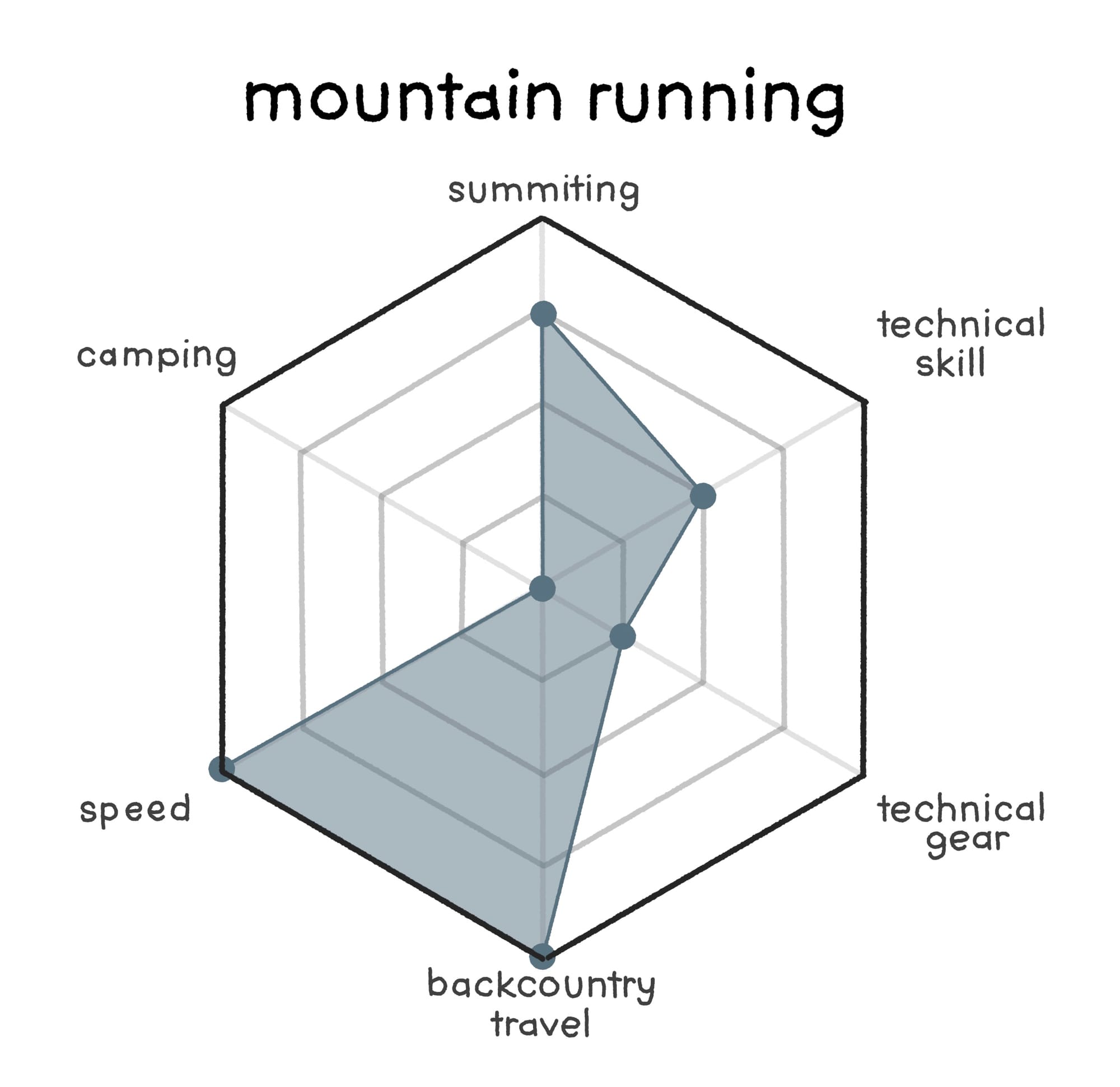

Mountain running (also known as "sky running", “adventure running”, or "ridge running") is a fork off of trail running that aims to include more technical backcountry terrain. Many trail runners may not even make this distinction today, and will call both their mild hill runs and fast and light ridge scrambles "trail runs", but the difference is noticeable.

Both trail and mountain running are distinctly focused on speed, tackling their chosen terrain as efficiently as possible using only their own body. The difference only arrives in the choice of terrain, mountain running takes place in arenas that combine 1st through 4th class trails, stringing on-trail and off-trail travel together, without bringing technical gear like ropes.

The lines begin to blur here between "mountaineering" and "trail running" as athletes get stronger and shared knowledge of backcountry areas pushes people to do more with less. I expect to see these terms thrown around more as the amount of new entrants to trail running rises and people want to distinguish themselves.

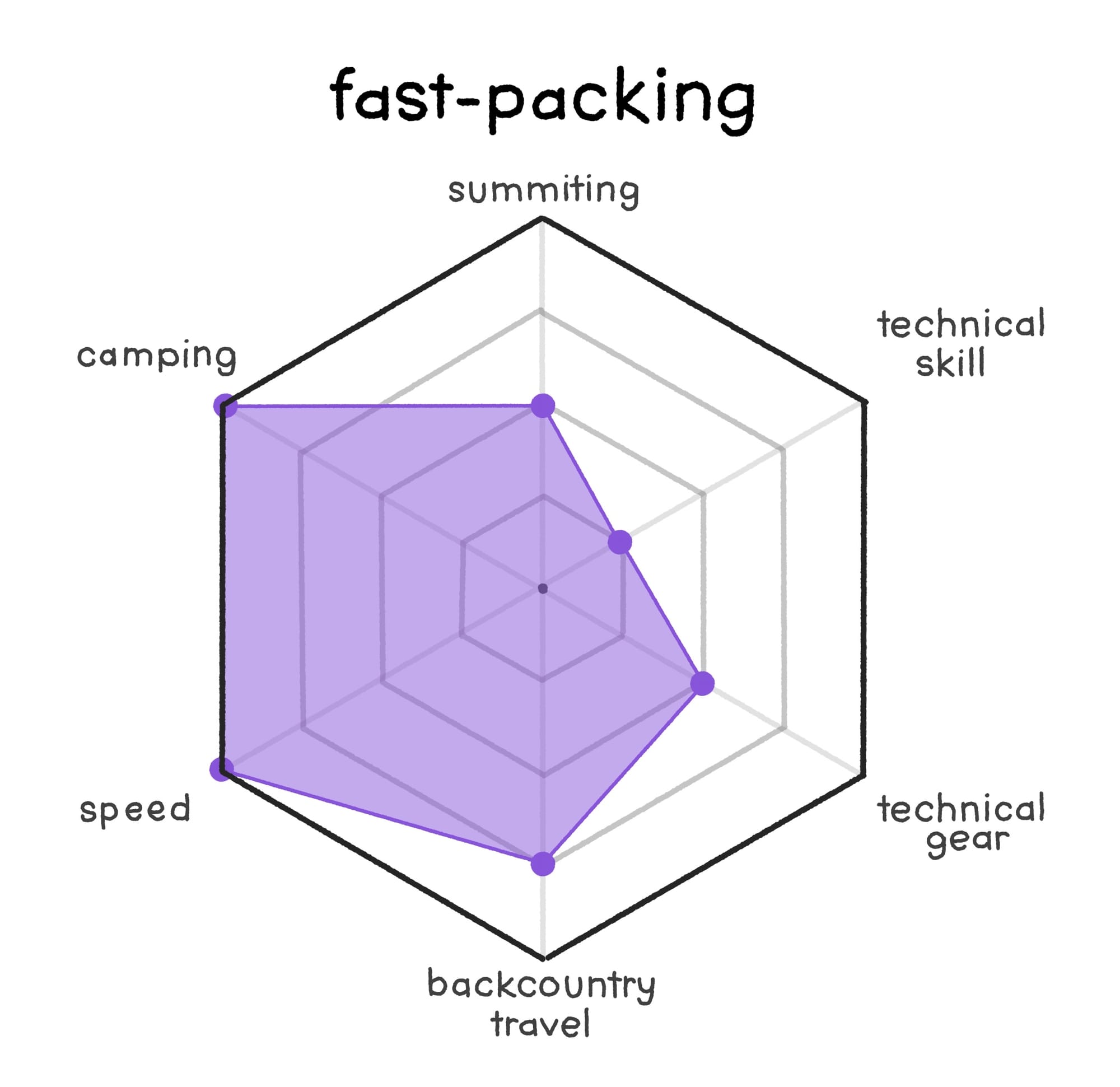

Similar to mountain running, fast-packing takes the new found speed and endurance of modern athletes and combines it with cutting edge light weight gear to bring backpacking into the fast paced mix.

Fast-packing focuses on speed while on multi-day excursions, often forgoing luxuries that backpackers (even ultralight backpackers) enjoy to cut their weight down dramatically. This enables them to run with their pack on, using harness style bags rather than traditional frame bags. In some very civilized places (Canada, Europe, New Zealand, etc) the lack of luxuries can be offset by utilizing hut networks, where food and shelter are taken care of and the fast-packer only needs to carry their clothes and weather gear. In America however, fast-packing is often more rugged, involving bivys (short for "bivouacs") where you make an improvised camp high on a mountain or ridge, typically without a tent. These pushes tend to only use sleep as a necessity to make it through long miles or difficult terrain that cannot be tackled in a single day.

Fast-packing is also often used in conjunction with "high routes" where one travels through rugged technical terrain (typically without 5th class climbing), staying up in the mountains and on ridge lines, rather than descending through valleys like one might while backpacking. These are also called "traverses", or when multiple peaks are reached in the course of a high route, "link ups". This niche overlaps with fast-packing due to the need to stay light to be able to scramble without a cumbersome heavy pack and tend to focus on keeping exposure to the elements to a little time as possible and doing long pushes over a few days.

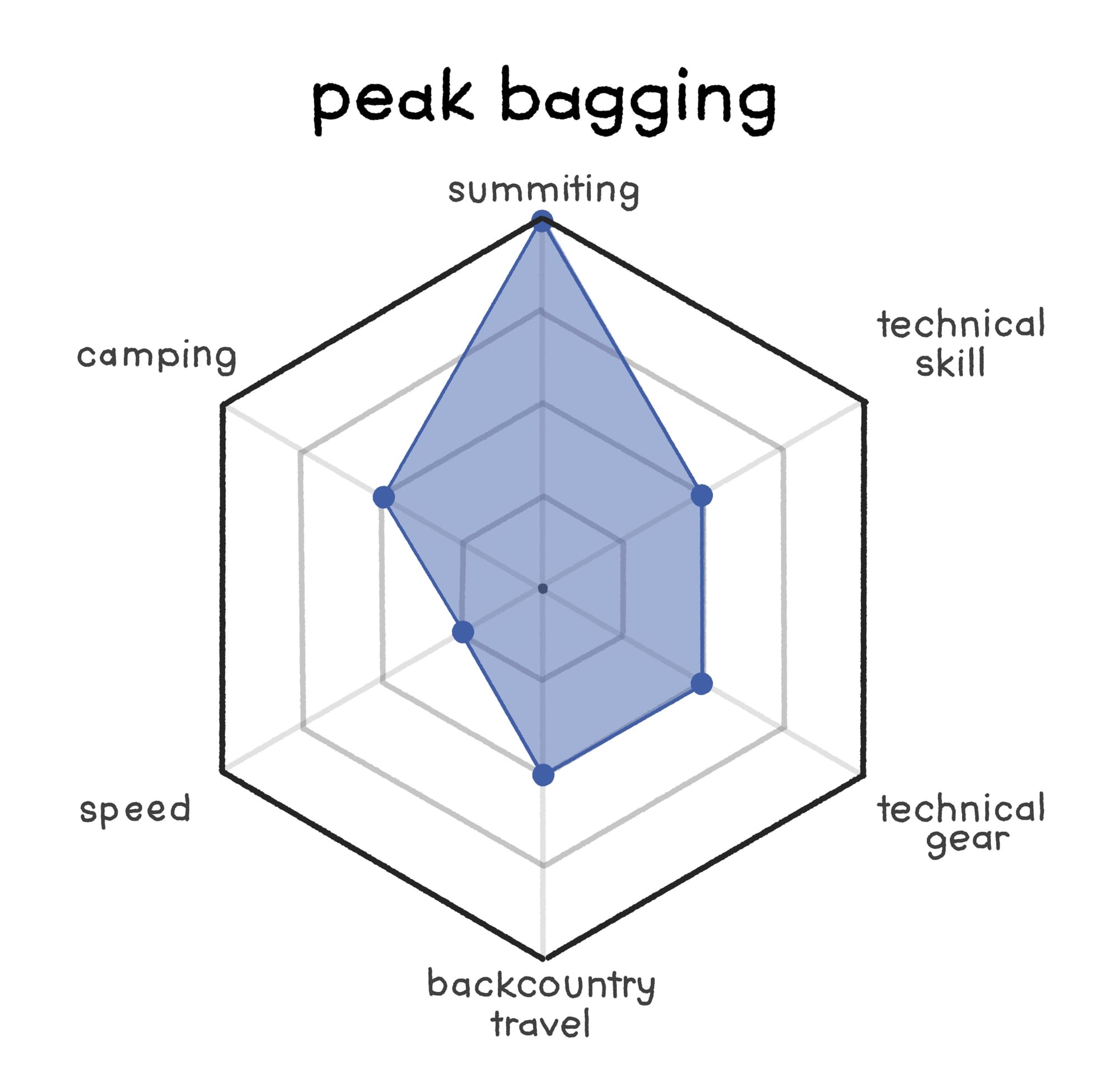

Peak bagging is a funny little niche forked off of hiking, where one has a strict focus on summiting as many peaks as possible. To a peakbagger, a hike that does not end in a summit is a bit of a waste. This was made popular in the internet age with sites like https://peakbagger.com/ or http://mountainproject.com/ where one can track their ascents against others in their community, though by no means is a new phenomenon (many could call all early mountaineers and guidebook authors peakbaggers).

In many ways this is not a sport of its own, but instead a mindset one might have while entering into one of the other sports highlighted here. This is why the graph remains well balanced across all of the focuses, many methods may be required especially when ticking off "harder" peaks which fall into the realm of mountaineering. However, many self-proclaimed peakbaggers would also say they are just hikers.

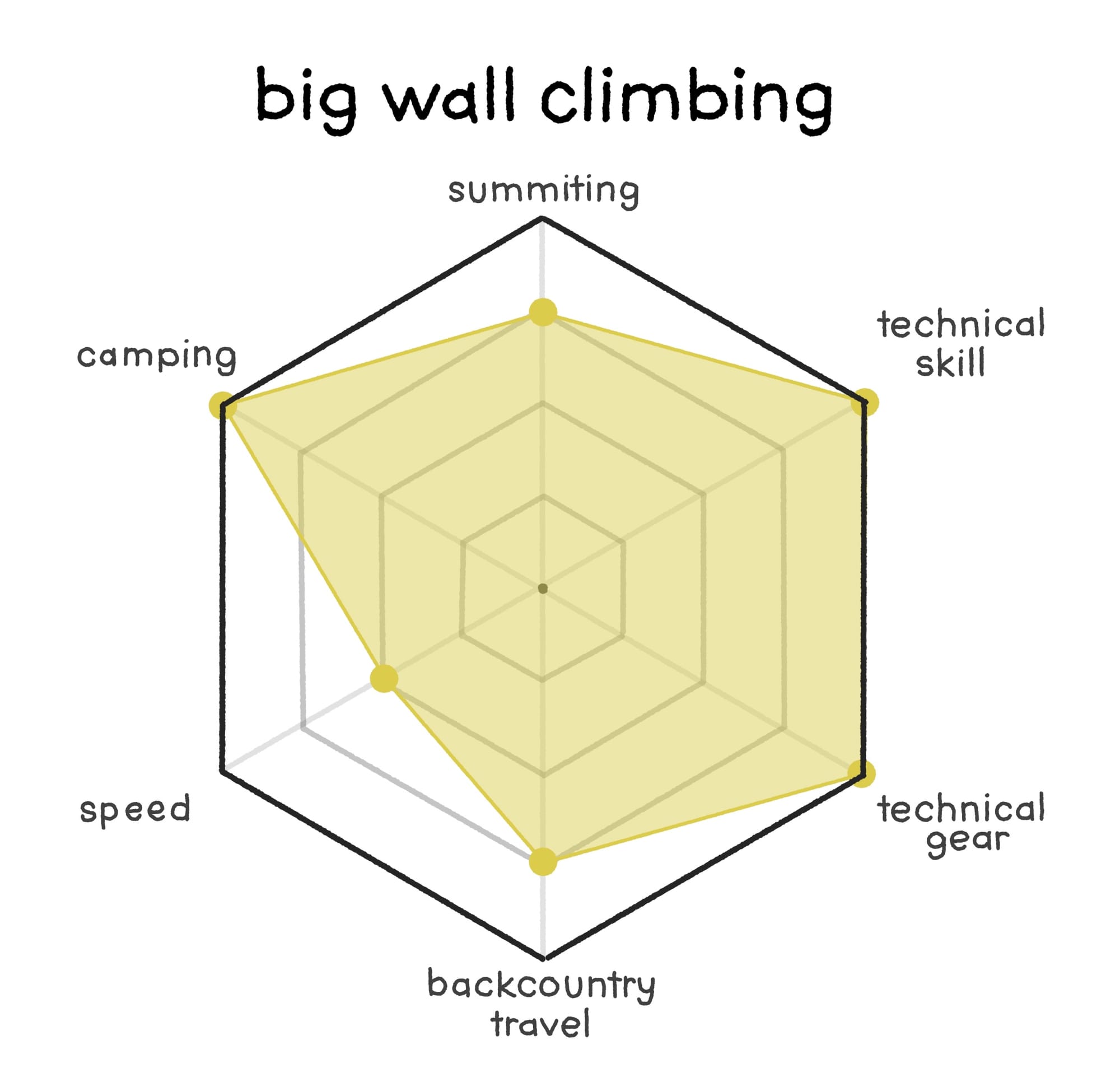

Big wall climbing is an intense off shoot of climbing that pulls in all of the aspects of backpacking, but made vertical. The most famous example of this is Yosemite's El Capitan, a single wall requiring 31 pitches of climbing to ascend. Most mortals can't achieve that in a single day (A "N.I.A.D", or "Nose in a day", is a great achievement for any climber) and must camp at some point along the wall.

Climbers will ascend the wall using their preferred climbing technique and haul up gear for multiple days using elaborate rope systems involving pulleys, static ropes, and massive tough haul bags. Whenever they are finished climbing for the day they will set up camp, either on ledges or suspended by extra specialized gear like portaledges (the fancy hanging tents you saw in "Dawn Wall") to ensure that they can safely and comfortably sleep.

These techniques are required when climbing huge (big) walls, especially when they have not been climbed before and exploration has to happen during the climbing.

But, Isn't There More?

There is a whole world out there in each of these "sports" I've described and many more I have not mentioned. Rabbit holes, disagreements, and new space to adventure in await on each of them. So, when you are talking to someone and you don't know exactly what they mean, don't be afraid to ask. People who are super deep into something tend to love talking about their passion and want to get others into it (those who don't are assholes!).

What are some sports or terms you have heard that you didn't understand? What are somethings I left out or left ambiguous? Let me know and I'll keep this series updated and we can build up a whole thesaurus of terms and graphics to explain the wild world of "mountain sports".