The Magic of Loops

The beauty and whimsey of loops as well as a trip report on the Ingalls to Fortune traverse

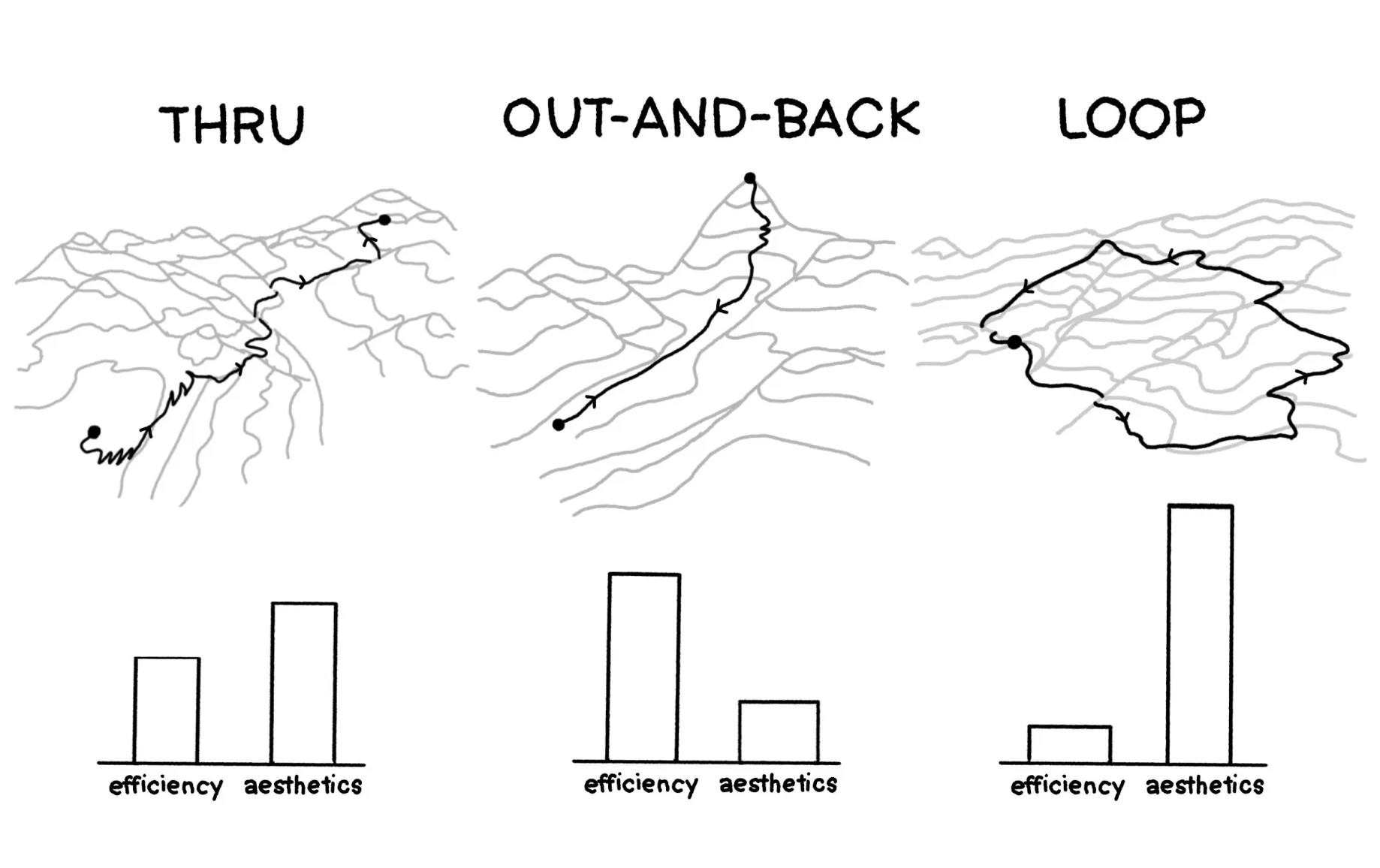

When you are creating a route (whether driving, or biking, or hiking, or running, or whatever) there are really only three configurations you can end up with: a point-to-point (thru), an out-and-back, or a loop. Out-and-back is the most efficient, getting you to a point - typically via the most straightforward path, and returning you to your starting location. This is what most of our trips look like, when you go to the grocery store, walk to work, hike to a mountain top, etc, we are just trying to get where we are going and come home. A point-to-point too can be efficient, but ends is up feeling rather impractical most of the time, dropping you far away from where you began. Its incomplete, a voyage without a return, or one reliant on a hitchhike being garnered back to your point of origin. Really a point-to-point is just a part of the last option, a loop. To embark on a loop intentionally is to be extraneous, to begin and end in the same point without an obvious target or destination. You can use loops to link multiple points together, but there will always be an aimlessness to wandering around, intentionally taking a longer path than is required.

There is a whimsey to this that itches at the simple, soft parts of my brain. For me it feels innate, some distinct and physical aesthetic quality, that becomes more and more pleasing the more "true" the loop is. To retread as little of the same ground is a sincere goal that bewitches me every time I look at a map. The joy of it is hard to describe, but experience after experience the loop has provided me with something that an out-and-back (or even the similar non-retreading point-to-point) can never quite replicate.

As I have thought more about why this might be, why I have such an inclination and fascination toward this arbitrary choice, breaking down trip after trip, I find myself left with a very simple (and personal) definition of "adventure".

To me an adventure is time spent finding your way, embarking into the "unknown", always seeing new sights, and never completely certain what you will find around the next corner. I've loved this feeling of adventure since I was a kid, it's one of the things that drew me to the outdoors was being able to have these kind of experiences out in the world. However, growing up I found myself frustrated or even bored with the way many of my excursions turned out, always dreading the "back" part of the "out-and-back" that all of the hikes I went on seemed to be.

At first I thought I just hated descending, but really it was the deeper feeling that the trip was transactional in some way that didn't feel right to me. It seemed like we weren't on the trail for the experience of being in the world, but instead to get to the end point, following the trail laid out in front of us, trading in effort for a peak or a view. It took me a long time to make this introspection, to realize I wasn't connecting with the place or the movement in a way that felt meaningful to me. Instead I had found my way to other pursuits that gave me that sense of connection, namely rock climbing. Climbing demands engagement with the wall in front of you, insisting that you learn and interface with the route to be able to make your way through it, the movement is the purpose of being there rather than a focus on one specific end point or goal. I always left feeling changed, that I had learned something about myself and the place after the experience. So when I stumbled into my first big loop and felt the same joy wash over me, I knew I had to dig deeper.

I know this sentiment isn't universal, after all how could it be when out-and-backs are so ubiquitous that they fill the endless halls of internet and guidebook trail recommendations? Perhaps for some there isn't the same longing for that same adventurous feeling I seek, instead replaced by a sense of achievement or just diverting them to different hobbies as I had. Perhaps some can find a deeper connection in ways that I just can't on an out-and-back. I think the truth is probably a combination of both and the fact that devising and traveling in a loop just takes a bunch of extra work! It's tough to find loops out in the world. Its akin to putting together a jigsaw puzzle, all of the pieces are there, but getting them together to find the greater picture takes patience and care. Luckily for those of us who do enjoy a good puzzle, they are plentiful, and as they increase in difficulty they also increase in quality.

So, for those of you who want to join me in the absurd quest to create "true" loops and revel in the aesthetics in our little walks in nature (and for those of you who don't I hope I have at least piqued your interest) here is a bit about my own process for planning out these loops, some of my favorite examples to highlight what's possible, and a recent quick trip report on a new favorite loop!

A World of Loops

To dive into the topic, I'll start by highlighting the general categorization I bucket routes into, to show that there are really loops for everyone! You have probably done a loop before, but an unfortunate fact is that geography doesn't often align with looped trails. This contributes to their scarcity which keeps most people from enjoying their wonders especially when hiking or running. The world imposes obstacles in the form of mountains, rivers, and park boundaries that can force us "loop-walkers" away from the paths of least resistance and into more difficult terrain. Luckily this isn't always the case, sometimes the dynamic is flipped and the world has loops laid out for us in the wild, ready to tackle.

These are the first, most common, and "easiest" category of loops – natural loops.

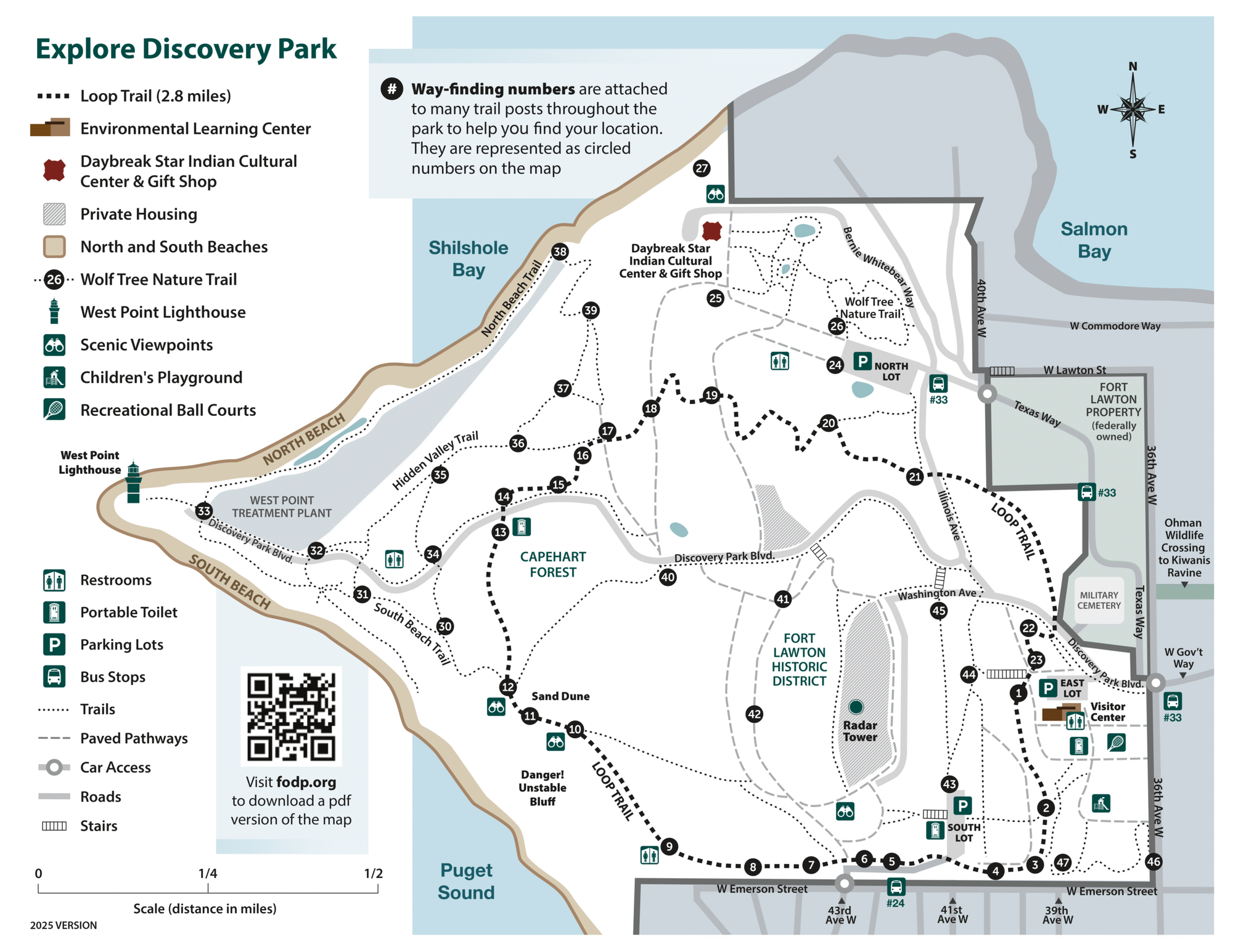

A natural loop is one that follows some obvious existing loop in the landscape. This could be a valley meadow, a lake, or a lone freestanding mountain, anywhere the natural splendor is already encompassed by a semi-flat area ready to be traversed. You may also find a less "natural" version tracing the border of most human-marked areas like parks (of any size) or even your entire neighborhood. Tracing some "longest-path" around them, winding at their edges. Either way this is the type of loop most people are familiar with because they are the easiest to discover and maintain! Some of my most common Seattle loops fall into this category, including the Discovery Park Loop and the Green Lake Loop – two named loop trails right in the city.

Green Lake holds three loops, all of them tracing around the lakes wonderfully round edges. Closest to the water is the named trail, 2.8 miles of paved path accessible to walkers, runners, strollers, rollerblades, and bikes (everyone!). The upper two loops, the protected bike lane separating the park from the road, and the gravel track that snakes along beside it, enclose the park and stay much less busy than the inner loop.

Another Seattle classic, Discovery Park's lovely trail system includes a named "Loop Trail" which traces around the edge of the "upper" park, following 2.8 miles of rolling dirt path winding through thick PNW forest and past incredible views of the sound and the Olympics beyond. You can add on the "lighthouse" extension to the loop and drop down to the rocky beachfront to get even more gain (climbing back up the stairs is brutal!)

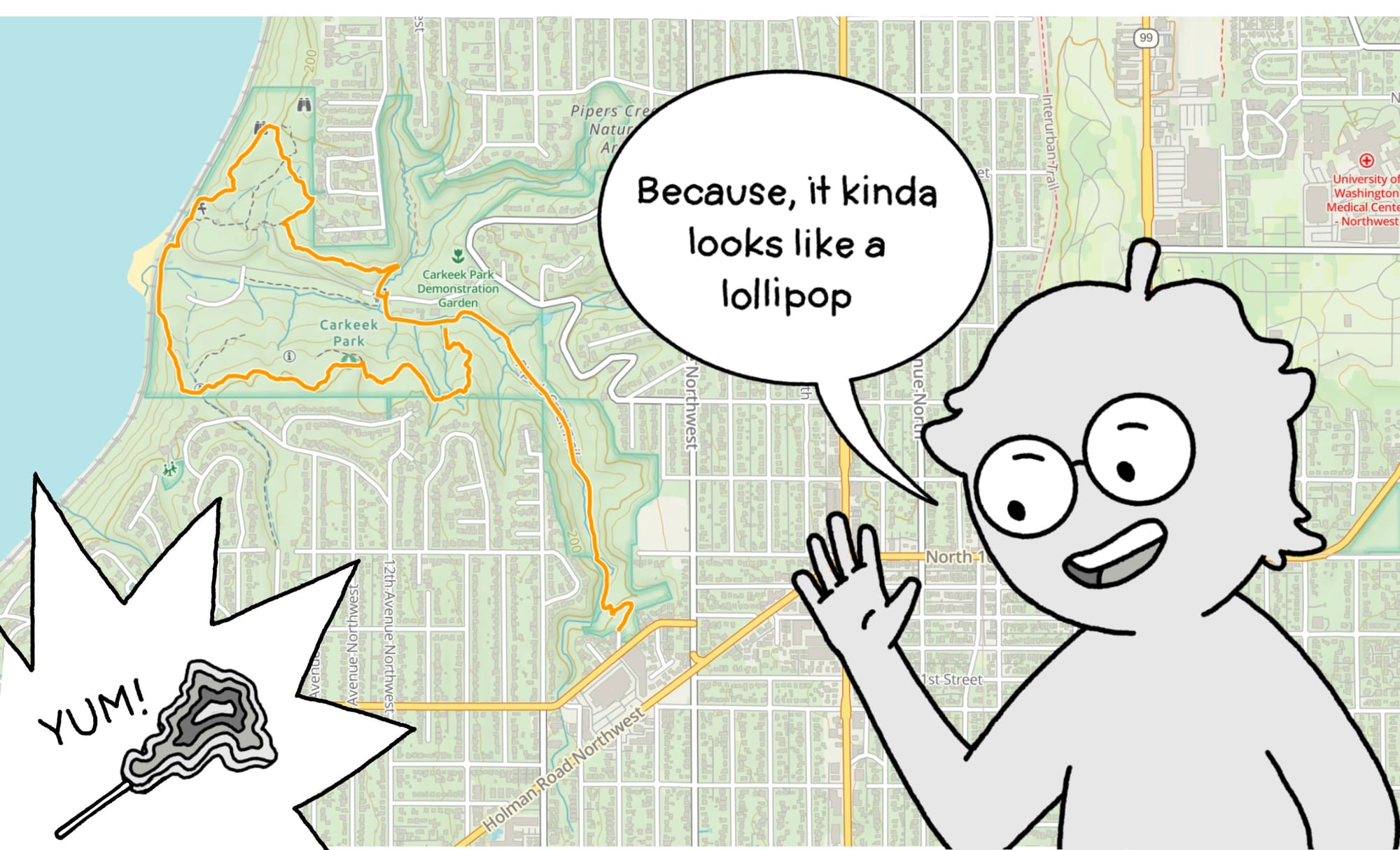

These city trails I often end up "lollipop-ing" from my house or one of the entrances to the parks which takes away a bit of the raw aesthetic on the map, but really makes up for it by not having to drive anywhere.

When we don't quite get a natural or maintained loop, we have to look between the lines, and piece them together from other non-looped existing trails. This works especially well in dense networks where paths criss-cross and overlap. In the city the street grids supply this easily, all it takes to make a loop is making four left or right turns spaced in your preferred manner. On trails we can find these kind of networks in many well maintained parks and public lands, places where loops lie dormant, they may not be labeled for us or available on our favorite trail-recommendation engine, but the tools are all there at our disposal.

These are the second kind of loops – combination loops.

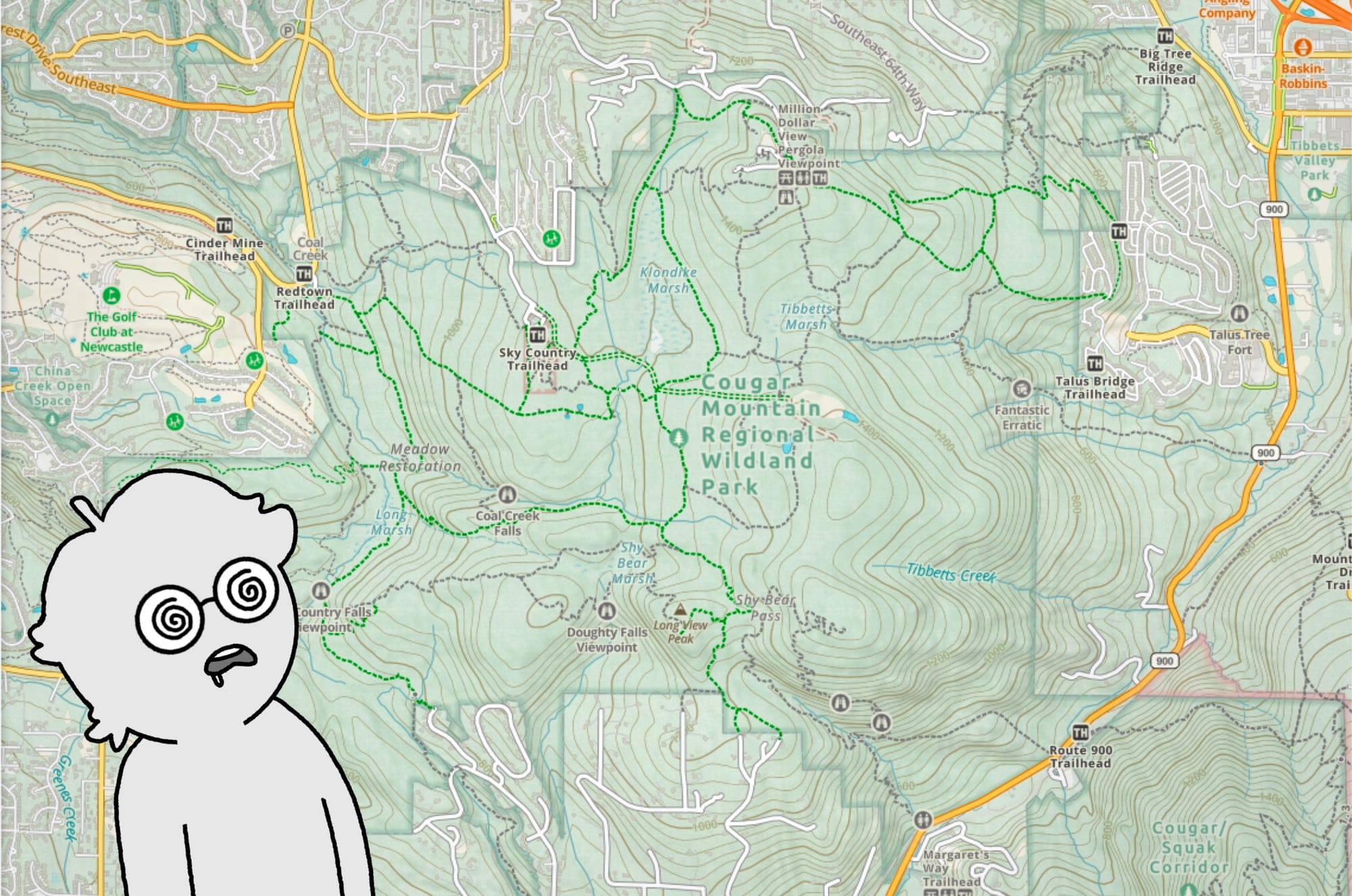

Combo loops take existing trails, often other thru or out-and-back trails that overlap at some point, and splice them into loops. In some places this can be really obvious to create, many parks with lowland areas, multiple points of interest, or with multiple entrances will have trails going all over the place. One of my favorite examples of this is Cougar Mountain in Issaquah.

Just look at that canvas! Because there are half a dozen trailheads surrounding the park, the trails spider out from every edge. We can see them join and cross in dozens of places where avid puzzle-solvers can make turn after turn to complete any number of loops. In this park I've created 6, 8, and 10 mile trails on this network to fulfill specific running distances I needed to complete that week.

If you want to make your own loop in a park like this, simply pick one of the trail heads and then track left or right, following the trails in that direction bringing it slowly around until you hit the mileage/gain you were looking for. Most mapping tools today have snap-to-trail functions and live estimates that make this a breeze (I have used Gaia for a long time - all of the screenshots are from there - but CalTopo, Goat Maps, and OnX are all pretty good tools) which is great since you will have to play around, creating a couple of options to really dial in what you are looking for.

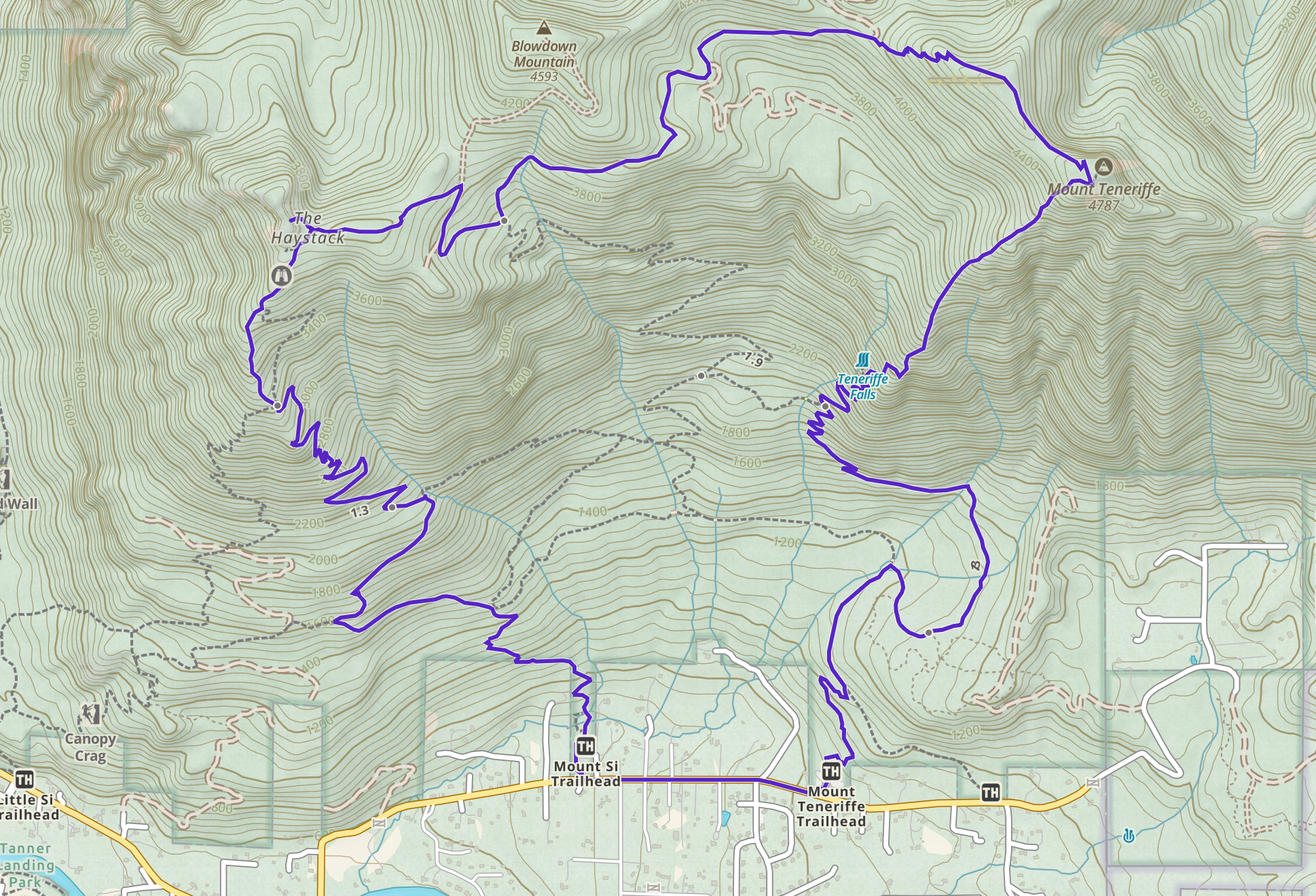

I've made a couple of big loops this way and one of my favorites is the "Teneriffe to Si Loop" in North Bend. Combining the "Kamikaze" Trail up Mt. Teneriffe (A marginally maintained trail going straight up the mountain) and then descending the main trail until you reach the shoulder between the two peaks where an alternate trail up the backside of Mt. Si forks off. Follow this fork up to the Haystack, do a little scramble, and then descend the Mt. Si trail back to the parking lot. Together they make an 11.5 mi loop with a bit over 5000 ft of gain, thats a big trail for the foothills of the cascades! It does require 3/4 mi of road running between the two trailheads, but this serves as a great warmup or warmdown for the day.

While combo trails are great as ways to extend existing trails or pick off multiple points all in one go, they can only get you so far, ultimately hitting gaps and blank spaces if you limit yourself to existing trails. Even when there are existing trails, you can often be led down convoluted paths requiring you to ascend and descent passes that are only slightly separated or to run miles on dusty forest roads.

If you are like me (which, if you got this far, you're probably at least a little bit like me) you are looking at the peaks and ridges just beyond the trails wondering why you can't go there. "If I could just descend the other side of this [peak/ridge/hill] I would be able to get to X" or "That ridgeline looks like it goes if that drop off isn't too bad" are thoughts that have crossed my mind far too many times while I'm out.

This is where the third category of loop comes in - adventure loops.

An adventure loop leaves existing trails behind for at least part of the route. Traversing open backcountry terrain by scrambling ridge lines, bushwhacking through wild country, or crossing snowfields/glaciated terrain. Making use of these features to access peaks or areas inaccessible from marked and maintained trails. Sometimes there will be "climbers trails" in these places, cairns or other vague markers left from other travelers. Sometimes there will be no signs at all.

This style of loop is where I have to warn any would-be copy cat that going off trail can be irresponsible and dangerous. You need to be confident in moving through the backcountry and half all of your exit strategies dialed in. Maps are only so accurate, reports can become outdated, and someone else's idea of risk can be way different than your own. I have been thwarted on routes by thick bushwhacking, loose scree fields, snow conditions, and required climbing moves. Each of which I was considering as part of my planning and either had backup plans or ways to bail. With that warning out of the way (heed it!) creating a route of your own that feels novel and takes you through seemingly untouched places is electrifying when successful. For each high point I have had completing one of these though, I have been through multiple failed attempts and hours of planning. It's part of the process and adds to the adventure, so let's step in to what these look like.

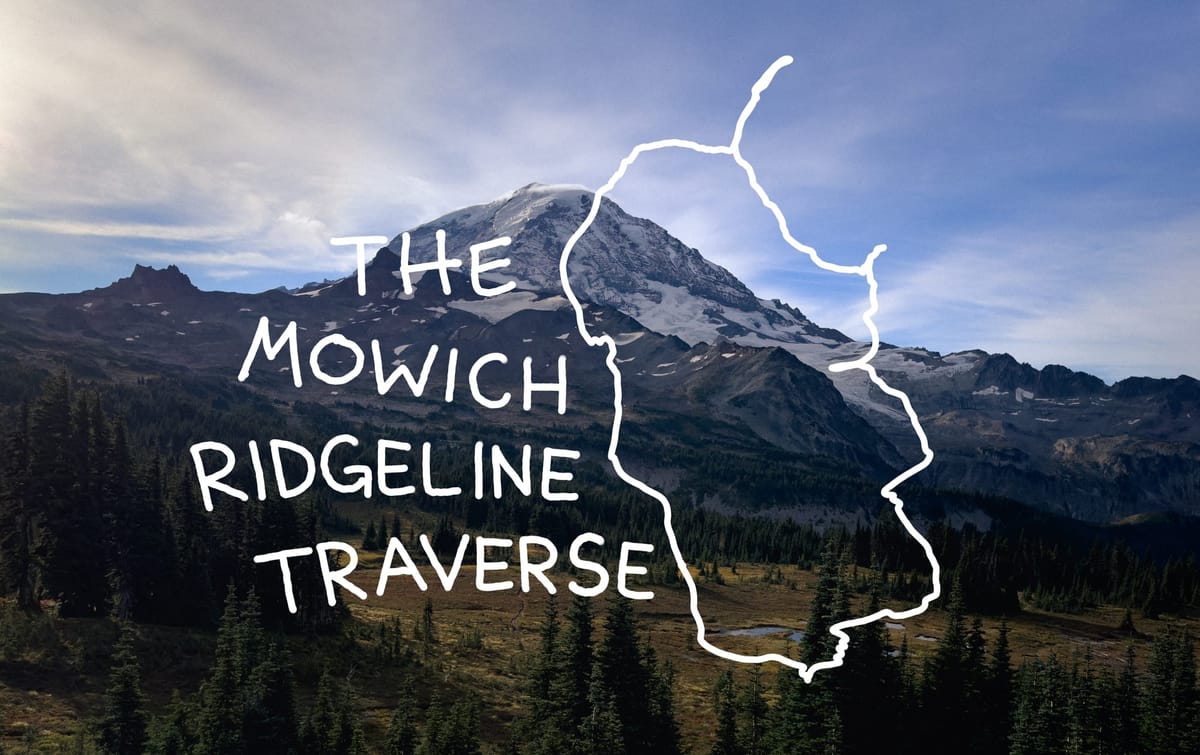

I wrote here about one of my first successful big adventure loops in late 2024, the "Mowich Ridgeline Traverse" where I scrambled between set of connected peaks on the Carbon Glacier side of Mt. Rainier. In preparing for this loop I found numerous reports for the individual peaks and even some for specific ridge lines, but nothing for the entire loop. This meant creating multiple GPS maps with alternative routes and having to route-find on the day. At any point if I was met with an obstacle that felt too dangerous I was ready to bail, I had already bailed on multiple similar trips earlier that fall when the trails got worse than they had appeared in my planning. It took all of those failed experiences to hone in my puzzle skills and bring this one to a close.

An Adventure Loop Trip Report

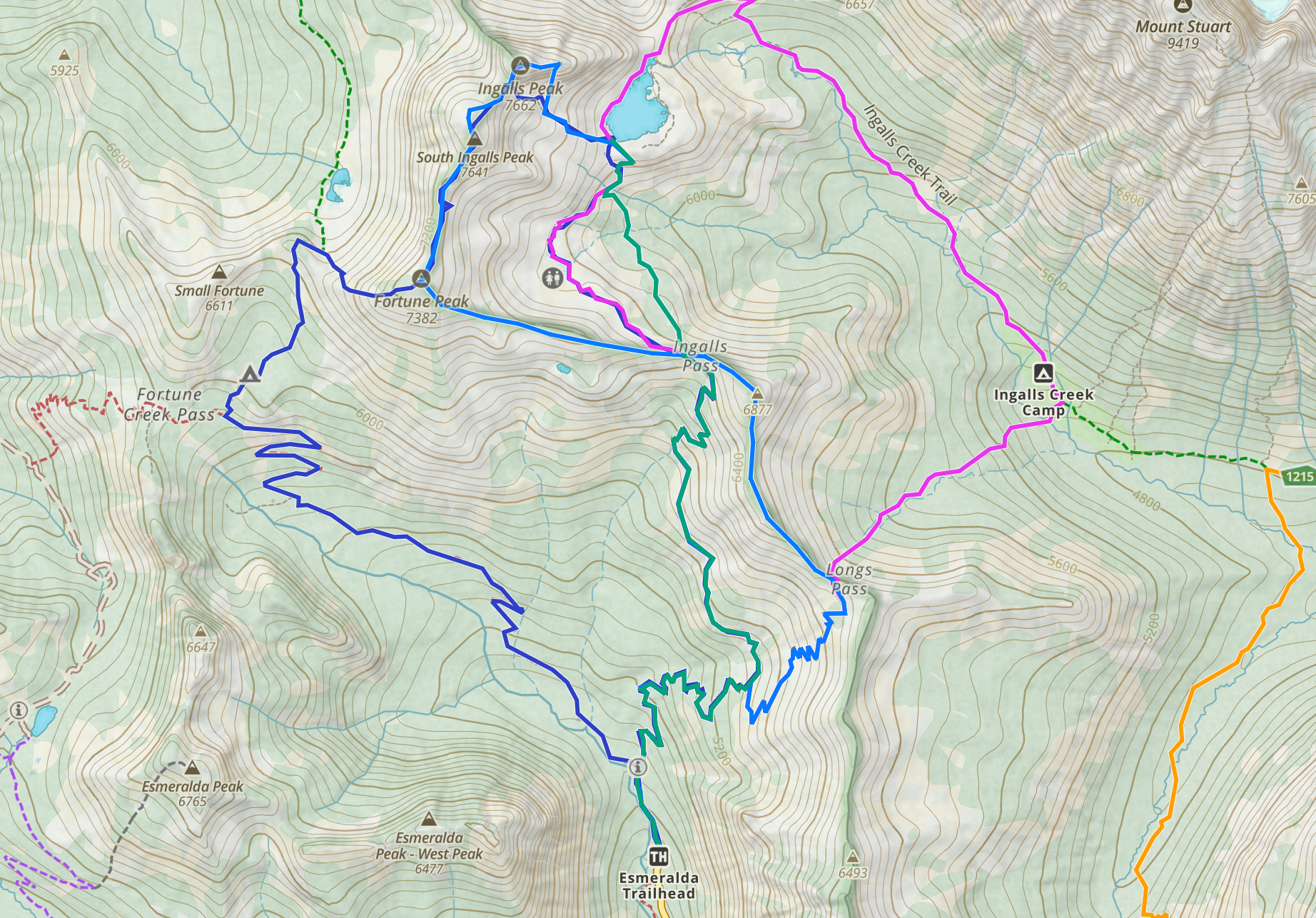

Last month I got to complete the Ingalls to Fortune Traverse, a loop I had roughly drawn on my map for months prior. Ingalls Lake is a classic fall larch hike, one that I had been on early into my tenure in Washington. Above the lake lies craggy peaks covered in sloping yellow and red slabs. I remember looking up at them and thinking it would be an incredible playground for scrambling. So when I started my journey making adventure loops, I scrolled over to this spot and started putting down frantic lines anywhere that seemed roughly passable. Luckily, this loop is not unknown, and reports of versions of it exist in multitudes online with pretty good descriptions and even gpx tracks.

So, I met up with a couple of friends at the Esmeralda Trailhead one morning in July, the clouds were high and wispy keeping temps enjoyable but rain at bay. We each had a light pack, ready to move as quick as we could over the varying terrain we would hit on the route. From the lot we ascended the well maintained trail up to Ingalls Pass where we could see our objective finally looming ahead of us, a long undulating and rocky ridge surrounding the valley on the west side. We took the high route to Ingalls Lake, stopping briefly to filter some water and admire the mountain goats that were grazing nearby.

From the lake the trail ended, we picked our way up through low angle slabs and scree washes to the craggy col between Ingalls and South Ingalls. We then traversed around the sharp rock fin that sits at the top of the col, passed underneath the south face climbing route (seeing two parties roped up enjoying the day as we were), and started finding our way up the "scramble" route around to the north side of Ingalls.

It immediately forced us onto some 3rd/4th class with moderate exposure, navigating between a chossy gully and some slick slabs up to an exposed step around. We were already feeling hesitant about the quality of the rock, but given we were doing to have to downclimb this section no matter what we continued on to see if it improved... just beyond that point it got worse. The route continued up a small gully like climb absolutely filled with kitty litter scree, and beneath it was a long fall down to the valley below. Not wanting to risk our lives to little rocks we decided that was our limit and turned around to immediately have to downclimb the prior section.

After managing the downclimb, very slowly and carefully, we were excited to tackle the route up to South Ingalls which already looked much more straightforward and with higher quality rock. The ridge butted straight into a large blocky rock wall, with a very slight trail traversing underneath it to a lower angle section to our right, but the climbing looked great up this direction, so we opted for some 4th class moves on good rock to mount the ridgeline from there. This let our route stay closer to the high point of the ridge which is another aesthetic quality that I look for on a route, both on the day in the movement it provides and on the map afterward. The climbing backed off after the first section and we were able to hike up the rest of the way to the south peak.

The peak offered incredible views of Stuart and the cascades to the north, as well as a great view of our route for the rest of the day. From here the ridge got rockier, and we hopped directly off the summit heading south through a narrow break in the rock. We stayed high and hopped across the rocks, swapping between 2nd-4th class movement. The exposure remained relatively minimal and we got a great flow going moving quickly through the terrain.

Eventually the choice to stay high put us on one section of semi-spicy downclimbing that could have been avoided by traversing lower around the rocks, but ultimately ended up being very enjoyable. From here we could see Fortune directly ahead of us and we hiked up to the summit to enjoy our last high point.

We saw a loose trail leading off of Fortune Peak back down toward Fortune Creek Pass, but it was indirect and the terrain was all open so we opted to surf down the scree on the west side of the peak until we met back up with the main trail leading down to the creek. We quickly dumped all of the pebbles out of our shoes and started an enjoyable run back below tree line and through Esmerelda Basin. We ended up finishing the outing in 5 hours and 45 minutes, covering 10.3 miles and 4100 ft of gain.

It ended up being everything I look for in a successful adventure loop. Fantastic views around every corner, flowy and fun movement over multiple types of terrain, and plentiful off-route travel (without the need for any bushwhacking) giving us endless options and solidifying the feeling of freedom that I only find on routes like these. Not a single part of the day was less than incredible, the true magic of loops come together. Classics like these are everywhere when you know the right people or how to look at a map with a bit of imagination, all it takes is a little dedication to a silly aesthetic ideal and the cumulative skills to tackle the terrain.

I hope these ideas have reached out to you and seeing trips like these inspires both my existing loop enthusiasts and some out-and-back purists to try this kind of adventure out once in awhile as a mindful practice. To go out into the world with a slightly more aimless attitude, less interested in specific destinations and more in the movement and journey you find while you are out. It certainly isn't the only valid way to enjoy the outdoors, and I hope I don't give anyone that impression (I'm finishing writing this as I pack for an out-and-back peakbagging mission) but it is one of my favorites.

Let me know what your favorite kind of adventures are, loop or otherwise, and I'll see you out there.